The ferry dropped us off in St Barbe, about two thirds of the way up Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula. It was late in the day and we decided to camp in nearby Flower’s Cove and head north in the morning.

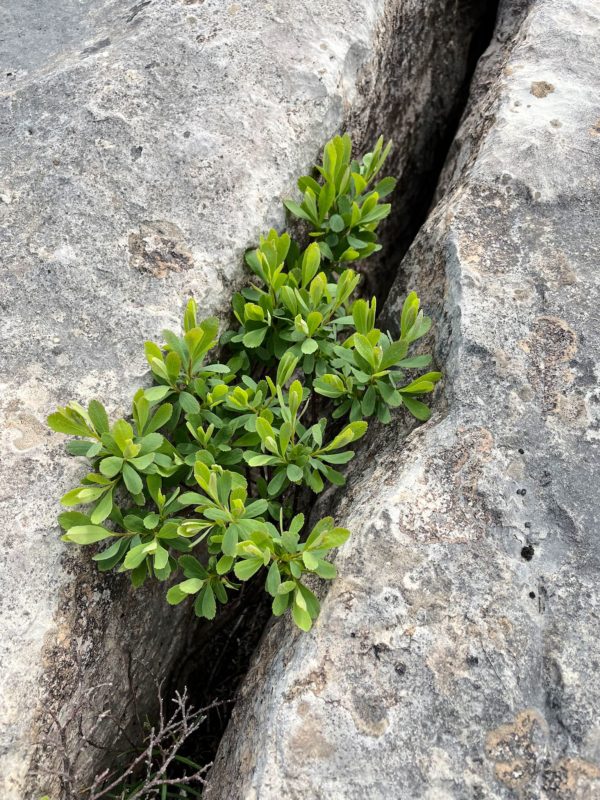

Our campsite was the trailhead for the White Rocks Trail. We woke to a cold fog, bundled up and investigated the relatively short hike before hitting the road. The White Rocks were giant limestone slabs flattened by the glaciers that cracked over time. Plants took root in the cracks, making them wider and deeper, eventually creating a rock garden filled with tiny, hardy flowers. Way to start the day!

St Anthony (pop ~2,200) near the northern tip is the largest town and service center for the Great Northern Peninsula. Although historically a fishing community where some fishing is still underway, the town has a decidedly different feel. It’s the site of the 50-bed Charles S. Curtis Memorial Hospital, many government offices, and several attractions that serve a lively tourist business. Our first visit was to the Visitor Center where very helpful staff provided brochures, maps and local intel on the town. They suggested a visit to Fishing Point, an end-of the road destination on the other side of town with a park and several walking trails. Sounds like a nice place for lunch…

Wow! A bank of fog was hanging just on the edge of the shore, fading in and out, daring us to get out and hike to Fishing Point Head, a prominence above the park and town. Glimpses through the haze hinted at spectacular views. We took the dare, and we lucked out! The hike up the Dare Devil Trail (>400 steps) and along the ridge was delightful. Views inland toward town were clear and gorgeous while views out to sea had a bit of fog adding visual interest.

We also hiked the short Whale Watchers Trail. Here, so close to the water, we thought the fog would win. Ha! We spotted a black marine mammal popping a fin in and out of the water quite near shore. I’m not a whale expert, however, I’m calling it likely a minke whale since it looked exactly like this. The trail ended at the Fox Point Lighthouse, next door to the Lightkeepers Cafe, which was highly recommended by our friends at the info center. We treated ourselves to dinner.

We’ve mentioned Dr Wilfred Grenfell, a physician missionary, in a prior post. Nearly every town we’ve visited so far on the Labrador and Newfoundland coasts has a Grenfell story. Traveling extensively from his initial headquarters on Battle Island, Grenfell eventually made St Anthony his home base as he expanded his mission. The Grenfell Interpretive Center included an overview of his life’s work. From 1890, when he first traveled in a ‘hospital’ boat to the small fishing and indigenous communities along the coast, until he retired in 1935, he lead an eponymous organization that developed 6 hospitals, 7 nursing station (like today’s urgent care centers run by nurse practitioners in small outposts), 2 hospital ships, 4 schools, 3 orphanages, 14 industrial centers to teach skills beyond fishing, 3 agricultural stations to assist the residents with growing food, 8 fisherman cooperatives allowing greater control of the sale of their fish, and an international organization raising funds and recruiting volunteers and staff for the mission. In 1981, all of the Grenfell assets were sold to the Provincial government for CA$1.00, and the Province continues to provide these services to residents.

We also visited the Grenfell House Museum, built in 1900. In addition to being the home Dr Grenfell built and shared with his wife Anne and three children, it was also used for work related to the mission. Teahouse Hill is a short hike up from the house. Both Dr and Mrs Grenfell’s ashes are buried there. It’s also a high vantage point from which to view the pretty town of St Anthony.

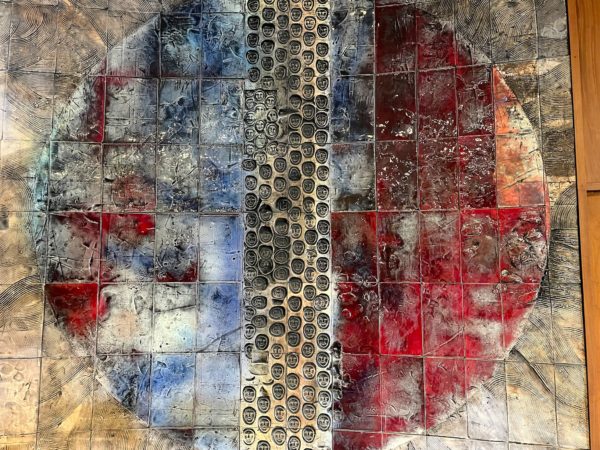

Grenfell supervised the building of a hospital in St Anthony in 1905. Over the years, it has undergone many expansions and upgrades, specifically related to the modernization of healthcare services. Today, it lives on as the 50-bed Charles S. Curtis Memorial Hospital. The rotunda of the hospital features 8 beautiful ceramic murals commemorating life in Labrador and Newfoundland, created by Jordi Bonet in 1967.

Of note, or of interest to us, at least, the Grenfells retired to Charlotte, Vermont – about an hour away from where we live. So perhaps we, too, can claim a part of the Grenfell story.

Not far from St Anthony is the famed L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site. We’d heard much about this reconstructed Viking settlement, yet it wasn’t until we arrived that we began to appreciate its unique significance in human history.

Anthropologists have determined that our species originated long ago in Africa, and, over the next 100,000 years or so, migrated north and west toward present day Europe, as well as east toward present day Asia, and south to Australia and New Zealand. Over more time, humans migrated from Asia across what is now the Bering Strait into present day North America, and eventually into South America. The Norse who reached the shores of Newfoundland and set up a base camp at L’Anse aux Meadows around the year 1000, and traded with the people living there, were the first Europeans known to visit North America, and, significantly, the first humans coming from the east to meet humans who had arrived from the west, thus closing a circle of migration around the world.

Tales of Norse exploration of North America had long been known to academics, and a search for proof all along the east coast had been ongoing. In 1960, Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad searched the L’Anse aux Meadows area for potential clues. It was George Deckerman, a local fisherman, who lead Ingstad to what was thought to be the remains of an old indigenous camp. Ingstad immediately recognized in the mounds signs of Norse building. Together with his wife Anne Stine Ingstad, an archaeologist, they uncovered ruins and found the proof needed to definitively establish L’Anse aux Meadows to be the earliest known Norse site in North America. Archaelogical excavation continues to this day.

In addition to touring the Interpretation Center, we joined a guided tour of the historic grounds. Noah, our tour guide and (*this is cool!>>) George Deckerman’s great-grandson, was passionate about the ruins and signs of Norse building and likely lifestyle of the Norse who visited. From research to date, it appears the Norse built a camp at L’Anse aux Meadows that they used as a base for exploring and exploiting the region for needed resources. Artifacts, firepits, and other signs of interaction with indigenous people suggest the Norse visited L’Anse aux Meadows about 3 times for a total of about 10 years over a 25-year span. The current theory is that the Norse recognized they were outnumbered by the indigenous people with whom communication was difficult and relationships unstable, and travel to this outpost on the shores of Newfoundland was costly and difficult, and the rewards made the effort hard to justify. It appears the Norse burned all of their structures when they left for the last time.

Once we reached the recreated Norse buildings, Noah turned us over the the villagers – Finn the merchant and his wife Thora – in period costumes who would interpret the sod house camp.

The structures were cleverly build to withstand Newfoundland winters. They were small, tight and well insulated with dense, thick peat walls and sod roofs. Chimneys in key places allowed for small fires for heat and light in each ‘room.’ There were very few women on these expeditions. Those that came to cook or weave (sails, mostly) lived in separate rooms. The crews of men lived in groups of about 25 in a 20 sq metres/225 sq foot rooms. The leader of the group (thought to be Leif Ericsson, though this cannot be proven) likely had his own residence, among some other perks. At the end of our camp tour, Finn and Thora headed off – in a definitely-not-period ATV.

We ended our tour with a pleasant hike of the Birchy Nuddick Trail traversing along the rocky shore over bogs and barrens, past small lakes, tiny, hardy flowers, and the remaining Norse visitors.

Fun fact… Most people know L’Anse aux Meadows as a Viking camp. Vikings were the bad guys, the Scandinavian pirates of the North Atlantic. The explorers who visited would more accurately be called Norse – people of medieval Scandinavia.

We took a road less traveled as we headed south on the GNP along the east side. The terrain was mountainous and dotted with large boreal lakes. We visited Conche, the heart of what’s known as The French Shore and/or the Petit Nord (Near North). The interpretative center in Conche, housed in a former Grenfell Nursing Station, showed the settling of fishing communities and the changes over time due to international battles and treaties. Originally a French seasonal salt cod fishing destination, a treaty with the British prohibited the French from settling or building houses on coastal land. They were allowed cod processing structures on the shore. Eventually, the French hired local people of English and Irish descent as guardians to watch over their interests over the winter. Eventually, these guardians settled the French Shore towns. Yes, the people of the French Shore today bear a hint of Irish accents!

The coolest thing we saw that nobody ever heard of was the French Shore Tapestry. Conceived by the artist Jean Claud Roy, with the development managed by his wife Christina Roy, the tapestry represents life in Labrador and Newfoundland from pre-historic times through 2006, when the tapestry was begun. The tapestry is 1 metres/3 foot tall and 66 metres/217 feet long! Once the many difference scenes were designed and outlined by the artist, it took 12 women a total of 20,000 hours of stitching over 3 years to create the tapestry. Photographs of the tapestry are not permitted, so we share none – you’ll have to go see it for yourselves! For anyone who’s interested, here’s more info, including a few authorized photos.

Back on the west coast of the Peninsula, Port au Choix is home to another National Historic Site. Starting in the 1960’s, archaeologists have identified evidence of five different eras of settlers here over the past 6,000 years, and they likely all had great fishing in common. The local limestone has helped keep the artifacts especially well preserved. At the Parks Canada Interpretation Center, we were treated to a guest – a caribou who’d wandered just outside a large window to capture shade from the building. Our visit ended with a hike through the limestone barrens, over the Crows Head with views of the St Lawrence and the town of Port au Choix, out to Phillips Garden, the southernmost know site of an Inuit settlement in North America.

The town of Port au Choix was eventually settled by the French. Since the cod moratorium, it is today primarily a shrimping community. I spoke with a local woman at the grocery store who mentioned the shrimping industry was now also in decline…

A fun fact… The French translation of Port au Choix is ‘choice port’ or ‘port of choice.’ It’s so pretty, it would be be my choice port. However, it was originally named by the Basques who had settled earlier. Port au Choix is a Francosized name derived from the original Basque name, which meant ‘bad anchorage’ – not so pretty!

We noticed a few cool features along many of the roads on the GNP. At random intervals along the highway we see what look like tiny, well manicured vegetable gardens. That’s indeed what they are! Newfoundland is essentially a big rock. There’s very little soil for cultivating crops. However, with all of the prep work for building roads through the rock, the roadsides were essentially rototilled by heavy equipment, and as weeds and other plants have grown and died, and all that goes along with that, the soil has developed to a point where, with some assistance or enhancement, growing a garden is possible.

We also noticed neat stacks or occasionally random piles of firewood, at equally random intervals. Many people on the GNP heat their homes with wood. Most of the homes are on the shore. Most of the trees (effectively all of the trees) are further inland. Since it’s easier to travel through boreal forest by sled in the snow (remember, the ground is spongy), people cut their firewood in the winter, haul it to the road with sleds, and leave it to dry stacked or piled until it’s needed.

The GNP is more mountainous than anywhere we’ve visited so far. Although just a small section of the GNP is on the Canadian Shield, most is not. Although a lot of us Americans believe the Appalachian Mountains end at Mount Katahdin in Maine, that’s just the end of the Appalachian Trail. The Appalachian Mountain chain is considered to end on Belle Isle in the Strait of Belle Isle, so it passes up as far as St Anthony and near L’Anse aux Meadows.

For anyone who’s interested, more White Rocks at Flowers’s Cove, Fishing Point in St Anthony, Grenfell, L’Anse aux Meadows, and Port au Choix pix…